To be intimate with the land, to have a sense of place, is to enclose it in the same moral universe we occupy, to include it in the meaning of the word community. In Marine Ecology class, summer students do just that, but underwater! Through detailed observation and inquiry, students foster a deeper understanding of how tropical marine ecosystems are arranged into a self-organized and complex hierarchy of patterns and processes. What follows is an example of a student’s field note written underwater, demonstrating a balance between ecological truths and the beauty of natural history writing.

Standing in proud and weathered sentry, a giant sea fan coral demands the attention of every eye that alights on Dive Site 3. In a scan of the primary producer residents of the rock, it would be an insult to the size and prominence of the sea fan not to take note of it before any other coral. More than a foot in height, the sea fan flaunts a hand-like display of five this blue veins. From these veins, innumerable smaller veins branch and criss-cross like winding tributanes, creeping upwards and outwards the way frost slowly encrusts a window.

But upon a closer look, the net-like continuity of the sea fan’s face is broken by a conspicuous interloper: a flamingo tongue, hugging the sea fan’s fourth finger with a kind of suctioned urgency. Pearly and smooth with rows of small brown dots, the flamingo tongue appears at first to be a decorative bead to complement the sea fan’s splendor. However, a glimpse of the blackened, dead trail shaking behind the flamingo tongue alludes to a slightly more sinister purpose. An immediate question comes to mind concerning the nature of the relationship between the sea fan and its trespasser: Is the flamingo tongue’s presence one or parasitism, in which is eats away the polyps of its host for no beneficial exchange? Or does the sea fan glean some hidden benefit as thanks for sustaining its bead-like guest?

The search for additional relationships between coral and other organisms brought me to a second sea fan. This one, a wide-mesh sea fan, lounged off the side of the rock like a pine branch laden with thick needles. Here, too, a flamingo tongue took up residence, interrupting the fuzz of 8 fingered polyps that distinguished this sea fan as an ahermatypic coral.

Next, my attention was drawn to a large, stoic-looking coral, which thrust up from the rock like a cactus. Strong and brittle, this coral twined like an intricate sculpture shaped from driftwood bleached on a beach shore. An absence of polyps made me suspect it to be a hard coral, which usually retracts polyps until night has fallen. A search through a coral field book revealed that this piece of drift wood art may have been a staghorn coral, part of the branching and pillar group.

In visual dialogue with the elegance of the staghorn, several sea plums lent their careless delicacy to the rock face. Drooping like weeping willow trees, the sea plums did not deign to display their polyps even to an inch-close examination. This absence made me wonder if the sea plume is a hermatypic coral, with polyps retracted during the day, or whether the polyps are simply too small or too inconspicuous for viewing.

Other corals, however, were not as shy about displaying their polyps. One particular sea-whip coral, straight and gray-stemmed, hosted a blossoming of white polyps that perfectly resembled dandelion seeds. The polyps dotted the sea-whip so abundantly that it look as though one could pluck the coral, blow on it, and scatter the seeds to make a wish come true.

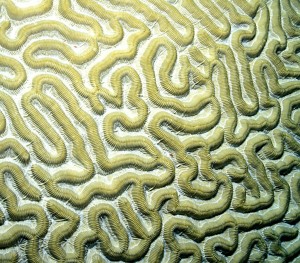

A careful tour around the face of the rock revealed a continue plethora of biodiversity. Spiraling elegantly, a rose coral appeared a bizarre juxtaposition of the most delicate flower and the specimen of some neurology medical lab. The tenuous folds of a brain coral resembled a labyrinth maze. Plump spheres of great star coral beaded the rock’s surface, and elliptical coral carpeted many areas in a patch work of pink polyps. Clusters of cup corals rose like white popcorn, lush flowers in a landscape of green.

Thanks Emily for this amazing piece of work!